In both work and life, we often hear the phrase: Collaboration creates strength. While this is an undoubtedly true statement, its obviousness can easily render it a cliché.

This phrase alone does not explain why collaboration is powerful, nor does it offer a clear rationale to convince others. Personal experiences play a significant role in shaping our belief in the value of collaboration, but experiences are inherently subjective and vary from person to person. Thus, even though the statement is valid, we frequently encounter situations where collaboration fails. So, where does the root of this non-cooperation lie?

To delve deeper and uncover the essence of collaboration, I will employ game theory as a tool for reasoning, while also referencing psychology to illuminate the psychological factors influencing cooperative behavior in practice.

1. Game Theory: The Strategic Nature of Collaboration

Game theory, a branch of mathematics and economics, studies the behavior of individuals or groups when making decisions in situations where the outcome of one party depends on the actions of others. The key here is that individuals make decisions based on their self-interest, but the final outcome is determined by the collective actions of all parties involved.

Every “game” in this theory consists of three elements: players, strategies, and outcomes.

- Players are the individuals or groups involved.

- Strategies are the set of actions they can choose from.

- Outcomes are the consequences of these choices, reflecting the benefits or losses for each party.

What makes game theory unique is its focus on strategic interaction: each player not only considers their own decision but also anticipates the reactions and strategies of others to optimize their own outcome.

Any situation composed of these three elements can be analyzed using game theory. Consider a simple and relatable example: the game of love.

- Players: Two people who have feelings for each other.

- Strategies: The ways in which they interact within the relationship.

- Outcomes: The result of how they execute these strategies.

From this example, it’s easy to see how different strategies in the game can lead to vastly different outcomes.

Collaboration in the workplace functions similarly. While each party may have its own objectives—such as timelines, costs, or quality—none can achieve success by acting in isolation. Each party must adjust its strategies to produce an outcome that benefits all, or at least minimizes harm for everyone.

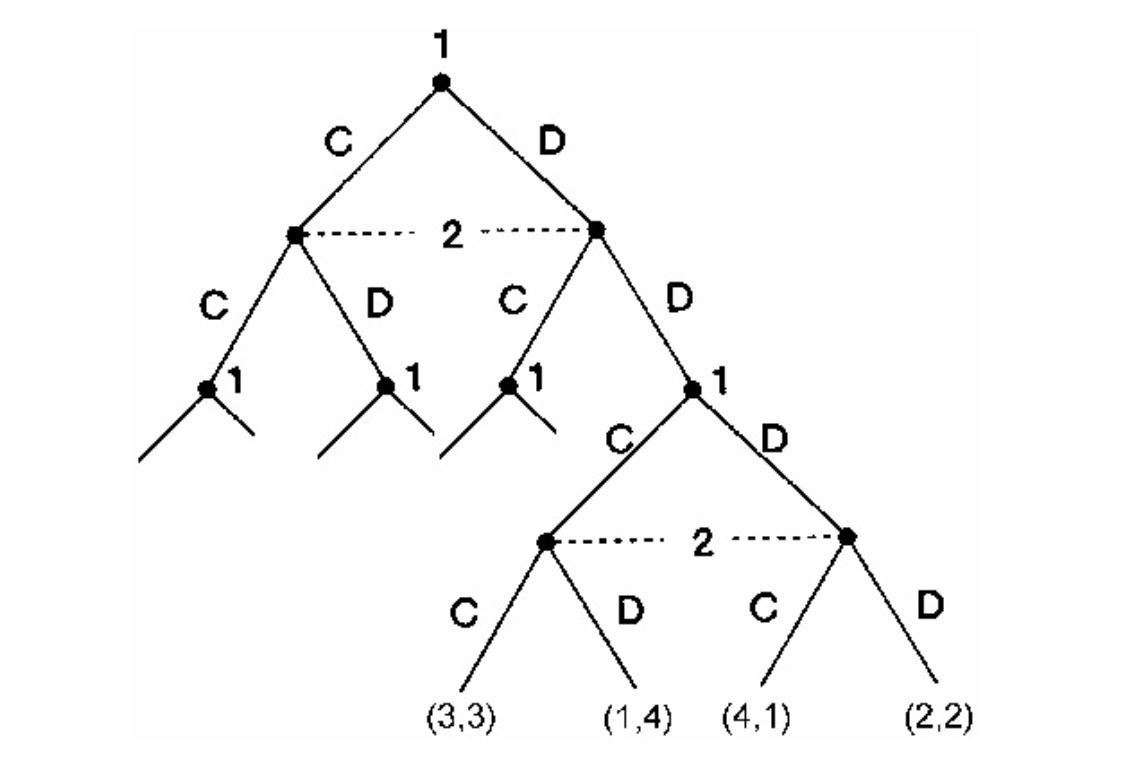

2. Demonstrating the Paradox of Cooperation: The Prisoner’s Dilemma

The Prisoner’s Dilemma is a classic example in game theory, clearly illustrating the challenges of cooperation.

Imagine two prisoners who have been caught after committing a crime, but the investigators lack enough evidence to convict them. They are interrogated separately and each has two choices: stay silent or betray the other. Several outcomes can arise from these decisions:

•If both remain silent, they each serve 1 year in prison.

•If one betrays while the other stays silent, the betrayer goes free, and the silent one serves 20 years.

•If both betray, they each serve 15 years.

This leads to the following matrix:

|

B1: Betray |

B2: Stay Silent |

|

|

A1: Betray |

15 years each |

A goes free, B gets 20 years |

|

A2: Stay Silent |

A gets 20 years, B goes free |

1 year each |

The contrast between cooperation and selfish behavior is stark: cooperation leads to a relatively light sentence of 1 year for both. However, selfish behavior through betrayal can result in harsh outcomes, with each serving 15 years if both betray.

This paradox underscores that while mutual cooperation yields the best result (1 year each), the incentive to betray is strong because neither can be sure the other will stay silent. As a result, both typically choose to betray, leading to a worse outcome for both—15 years in prison.

This dilemma highlights a critical paradox: collaboration always produces the best outcome for everyone, but trust is a prerequisite for cooperation. When trust is lacking, parties often resort to selfish actions to protect their short-term interests, leading to collective failure.

3. Cooperation at Work: The “Game” of Stakeholders

Applying game theory to the workplace, let’s consider a hypothetical Product team model consisting of three core roles: Designers, Engineers, and Product Owners (POs)—this is no different from a complex strategic game.

To start the game, each group has its own priorities, and when each side satisfies these priorities, it means they have ensured the requirements of their jobs—those things they are paid to do. In this scenario, we assume that three main groups participate in the completion of a project:

- Designers want to ensure the product meets user needs and provides the best experience.

- Engineers focus on implementing technically feasible solutions within the allowed time.

- POs prioritize timelines and revenue, wanting the product to launch on schedule to maximize business effectiveness.

The strategies of the parties are as follows:

- Designers can choose:

- D₁: Stand firm on design and user needs, demanding complex solutions to optimize experience.

- D₂: Be flexible according to Engineers’ requests, simplifying details for technical feasibility.

- Engineers can choose:

- E₁: Follow the complex requirements of Designers, leading to extended development time and potential errors.

- E₂: Simplify designs for easy implementation but fail to achieve optimal user experience.

- Product Owners (POs) can choose:

- P₁: Push for product launch regardless of trade-offs in quality and user experience.

- P₂: Balance between speed and quality, trying to harmonize the demands from Designers and Engineers.

Similar to the Prisoner’s Dilemma, each party has incentives to optimize their own benefits:

- If Designers demand many complex features (D₁) and Engineers also add unnecessary solutions (E₁), the project may be delayed and fail to meet POs’ requirements.

- Conversely, if Engineers oversimplify (E₂) to ensure timelines, the product will lack user appeal, leading to POs failing in revenue.

A matrix can be created based on the information available about this game:

|

E₁ (Engineers complicate) |

E₂ (Engineers simplify) |

|

|

D₁ (Designers demand complexity) |

P₁ (PO pushes roadmap): – Result: Major failure. – Poor UX, product errors due to insufficient time for complex designs. – Engineers overwhelmed, project fails in quality or timeline. |

P₁ (PO pushes roadmap): – Result: Poor quality. – Product launches on time but is oversimplified, UX does not meet user needs. – Designers dissatisfied, product fails in the market. |

|

P₂ (PO balances): – Result: Good quality but delayed. – Project completes with satisfactory UX, but timeline is not ensured as Engineers take time to fulfill high requirements. – POs accept delays to ensure quality. |

P₂ (PO balances): – Result: Acceptable. – Product launches on time but UX is not perfect. – Engineers complete easily, but user experience quality is only average. |

|

|

D₂ (Designers flexible) |

P₁ (PO pushes roadmap): – Result: Project overload for Engineers. – Designers adjust flexibly to reduce complexity, but Engineers still face challenges. – Product launches quickly but with low quality and many errors. |

P₁ (PO pushes roadmap): – Result: On schedule but reduced UX. – Engineers complete quickly due to simplified designs, but the product does not achieve the desired user experience. – Revenue does not meet expectations. |

|

P₂ (PO balances): – Result: Good balance between factors. – Designers and Engineers collaborate well, each conceding to ensure the product has stable UX quality and meets technical requirements. – POs satisfied with both speed and quality. |

P₂ (PO balances): – Result: High success. – Product launches on time, both UX and technical quality meet requirements. – All parties satisfied with the outcome, project succeeds in revenue and user experience. |

To make non-cooperation yield worse outcomes, the level of conflict and project failure can be heightened when each party acts solely on personal interests:

D₁ + E₁ + P₁ (Each side is selfish):

- Designers: Stand firm on user experience, demand complex designs, and refuse to compromise.

- Engineers: Follow complex demands, but due to the high requirements, the development drags on, resulting in poor code quality and many bugs.

- POs: Focus on pushing the product to launch, forcing other parties to release despite poor quality.

- Result: The product is launched with extremely poor quality, many technical bugs, a bad user experience, and prolonged development time, leading to a drop in revenue. A significant failure in all three aspects: user experience, technical quality, and business revenue.

D₁ + E₂ + P₁ (Designers too rigid, Engineers refuse):

- Designers: Continue to hold firm on user needs and demand complex changes.

- Engineers: Refuse the designer’s demands and try to simplify the design to ensure code quality and progress.

- POs: Focus on pushing progress to launch quickly, ignoring user demands and product quality.

- Result: Although the project may launch on time, user experience is poor, customers are dissatisfied, and long-term revenue is unsustainable. The project fails because it does not meet user expectations and fails to create long-term value.

D₂ + E₂ + P₁ (All three are flexible to their own interests):

- Designers: Accept design simplification to meet the timeline.

- Engineers: Self-optimize to reduce workload and ensure good code quality.

- POs: Push for a quick completion to launch the product, disregarding user experience.

- Result: The product launches quickly and meets short-term revenue goals, but user experience is poor, and product quality is affected in the long term, leading to the loss of potential customers. The project fails in the long term as customers abandon the product.

In contrast, if the parties cooperate and adjust their strategies to balance common interests, the project has a higher chance of success:

D₁ + E₁ + P₂ (Cooperate together):

- Designers: Stand firm on user needs but are willing to negotiate with engineers on some complex aspects.

- Engineers: Follow the designer’s plans but with PO support to adjust the timeline and resources.

- POs: Balance the demands of designers and engineers to ensure progress, quality, and user experience.

- Result: The product is launched with high quality, good user experience, and a balance between progress, technical quality, and user needs. Sustainable success is achieved both in terms of user experience and revenue.

Only when all parties adjust their expectations and strategies to compromise can the project have a chance to succeed. Coordination is the most important factor: each group needs to understand that optimizing their own benefits won’t lead to sustainable results if it harms the common goal.

It can be said that if all players try to win their own small game, the consequence is that they all lose the big game.

4. Cooperation and Psychology: Trust and Intrinsic Motivation

If game theory helps us understand the strategic mechanisms of cooperation, psychology provides answers to the question: Why don’t people always choose to cooperate, even when they know it’s the best option?

A key factor is trust. When parties do not trust each other—whether in terms of capability or intent—they tend to choose defensive options, acting in their short-term interests rather than cooperating to achieve a better outcome. This is why transparency and clear commitment between parties are prerequisites for building effective cooperation.

Additionally, intrinsic motivation (the desire to do good work) and extrinsic motivation (external rewards or pressures) also affect the willingness to cooperate. A healthy work environment not only needs to encourage collaboration through reward policies but also create emotional connections and shared values among members to maintain long-term motivation.

5. Conclusion: Cooperation is a Game of Trust and Strategy

Game theory shows that cooperation always results in the best outcome for all parties, but it doesn’t happen naturally. The success of cooperation depends on trust, transparency, and continuous strategic adjustment. In the workplace, if each group focuses only on its own goals without considering the needs of others, the project will face failure.

Understanding the principles of game theory helps us view cooperation not as a “nice to have” but as a critical condition. From this, it becomes clear that it’s not just cooperation that brings strength, but conscious and strategic cooperation. In a world where individual and common interests are intertwined, cooperation is the art of balancing and synchronizing goals—an art we must continuously learn and perfect.